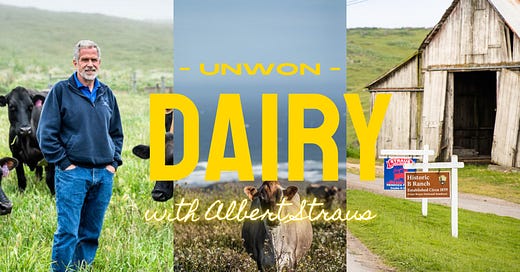

Albert Straus is a legend in organic farming and the regenerative food movement. He is the founder of Straus Family Creamery, the oldest certified organic creamery in the United States.

He has been an outspoken advocate and champion for the farmers and ranchers on Point Reyes, fighting tirelessly for his neighbors. His creamery sources milk from dairies on the peninsula.

In 1940, there were 4.6 million dairy farms in the U.S. Now there are less than 26,000.

The ranchers being evicted from Point Reyes are gagged. Straus shares his perspective after years of watching Marin County and California change around him—from a cutting-edge haven of organic, ethical food production to a “playground for billionaires” hostile to the small farmers and ranchers who made Marin special.

Q&A with Albert Straus

Condensed and slightly edited for clarity in written format from two interviews with Mr. Straus. Listen to our conversation in the video above or stream on Apple Podcasts.

Albert, thank you so much for joining me today. I appreciate you being here and speaking for the ranchers on Point Reyes since they really can't speak for themselves.

Thank you for having me, Keely.

Let's start with you and your background. Straus Family Creamery is, I believe, the first organic creamery in the United States. Is that right?

My dairy farm, which is not on Point Reyes but on Tomales Bay, was the first certified organic dairy west of the Mississippi River, and our creamery was the first 100% organic creamery in the United States back in 1994. Since then almost 90% of the dairies in Marin and Sonoma County are certified organic.

My family has been running the dairy since the 1940s. We stopped using herbicides in the 70s, and I began using no-till planting methods in the 80s. We developed this whole organic farming community. Prince Charles, before he was King Charles, visited Marin on his honeymoon with Camilla because of his interest in organic farming.

You’ve been a vocal advocate for the Point Reyes ranchers. Why have you been working so hard to help them?

My mission and the mission of the Creamery is to help sustain family farms in Marin and Sonoma County by providing high quality organic dairy products that are minimally processed and to help revitalize rural communities for education and advocacy everywhere.

We've seen a demise of our farms. In 1940, there were 4.6 million dairy farms in the United States. Now there are less than 26,000 left.

Smaller family farms are in a rapid decline, as well as our rural communities. We're losing the basic ability to produce high quality food locally and keep our communities together. We're on the tipping point of losing everything. So for me, it's my home, it's my business, it's my livelihood, and the community I love.

They’re saying that we're polluting, we're inhumane. Animal certified organic standards address animal welfare. We're all under very tight environmental controls and permits, and so there's no pollution. All this made-up science and lawsuits against farmers is just to drive them out of business—mainly livestock and dairy farmers. I do not understand why people are attacking their own food system.

How have you watched Marin County change?

My father started our dairy farm in 1941 and my parents worked their whole lives to facilitate a dialogue between farmers, environmentalists, community members, and government to come up with a common vision and strategy for the future.

My mother was a co-founder of the first agricultural land trust in the nation, Marin Agricultural Land Trust or MALT. And since then, they've preserved over half the farmland in Marin County to stay in agriculture in perpetuity.

We supported the formation of the Point Reyes National Seashore because it had a balance of agriculture, wilderness, and reintroducing some elk to a preserve. We supported the Coastal Commission formation to preserve the coast because it had that balance—to protect and promote agriculture and rural communities along with public access and tourism.

But it's become very polarized towards open space and tourism at the expense of the community, farms, and food production.

When Point Reyes National Seashore was created, it was with the vision of maintaining agriculture in Marin County, correct?

The Seashore had in its founding legislation a pastoral zone that was supposed to be agricultural, and that was supposed to continue on. We saw it as a positive way to preserve our community identity and prevent over-development. There’s been a narrative that this was never meant to be, but that’s not accurate. It was about 25% of the agricultural land in Marin County agricultural output. We’re losing all that. We’ve lost it over the past few decades because of the pressures that the Park Service has put on these farms to restrict their ability to have a business and be able to stay in their houses.

You were in Paris last year, you’ve led the climate smart movement in dairy, you’ve been a huge part of the regenerative agriculture movement. These are our ideal farms and ranches that we’re losing.

I’ve been working on an organic carbon neutral farming model for the last couple decades. We have a program for all our 13 dairies to be carbon neutral by 2030 off of practices. We’re well on the path—my own dairy is over halfway to carbon neutrality, where the milk coming from our dairies will have an equal or lower carbon footprint than any plant-based dairy alternative.

Last October, the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and the International Dairy Federation asked me to come to the 2024 Paris World Dairy Summit to sign onto an international declaration of collaboration around climate change and sustainability in dairy.

In the next 25 years, we have to produce as much food, to feed almost 10 billion people, as we have in the last 10,000 years combined. Dairy and livestock products are essential nutrients to feeding the world, and local production is essential so we’re not shipping food all over the world.

The fact is we're importing most of our food into the United States now. It's not sustainable.

What we're doing in Marin County and Sonoma County has been a model for the world. We've had a history of working together. Now we're polarized as a society. We need to get back together to move our food and farming system forward.

Do you think that the Park Service has welcomed ranchers? Or do you think that the Park Service doesn't see their mission as compatible with agriculture?

I think that it's the latter. The Park Service and these organizations have a very different view of parks and open space.

We’re seeing land trusts and county, state, and federal parks taking animals off. I found out the California State Park System doesn't allow grazing of any kind, even by goats and sheep. Historically, we've always had cattle grazing, which created income for the state. Now they have all this dry fodder that is just primed for wildfires. We have fires that cost billions in damages and people’s lives. Wildfires account for 2.5 times the amount of carbon in the atmosphere as all fossil fuel emissions.

I think that we haven't done our part to educate the public around farming and how food is produced. We need to get back onto a track where we're educating the public, showing them how we farm, that we do it humanely, we don't pollute, and we have a system that's really an example. That’s something I really want to take on as part of the solution.

We also have to stop farms being a target of lawsuits meant to drive them out of business. This litigation around Point Reyes has displaced all these families and farms. They say, well you have 15 months to leave. That's not enough to start another farming operation. There's a lack of understanding that farms can't be just moved from one place to another overnight. It takes a long time.

So I think there's a disconnect about what it takes to farm, what are the benefits of it, and how do we work together and support a local farming and food system that’s really been sustainable.

California wants to put organic food in all public schools, yet they're not working together with us to help that happen. We're losing farms and we're short of organic milk now, across the country.

What can you say about the pressures the farmers have been experiencing for the past few years?

Water quality samples were taken during a drought when they had no water flowing in the creek, to say that the dairies were polluting. They used that to create more regulations, more pressure on the dairies. They reduced the number of animals they could have on their land with no data to support it. Actually they should have had a lot more animals. So they couldn't have enough animals to make an economic unit.

They did not allow pasture improvement, either seeding or mowing. They ended up taking silage land away, so the farmers had to be reliant on outside feed. There was infrastructure they weren't allowed to improve—roofs and a lot of the houses. When there were problems with the septic systems that the park was supposed to fix, they blamed the farmer. And then the elk had been just not managed and released on all of the farmland, which cost one dairy over $100,000 a year just to feed them because they took the alfalfa hay from the cows and broke all the fences and ate all the pastures.

It's been a constant, long-term pressure. They wore these farmers out. When they came in with a settlement, I think that was the best outcome that the ranchers could see because the Park Service was not a landlord that worked with them.

Do you think that these environmental groups were complicit with the Park Service in trying to get these ranchers out?

The environmental groups sued the park three years ago for the second time. The ranchers and dairies joined the lawsuit on the side of the park. But the park was negotiating against them.

In mediation there's supposed to be a middle ground. The ranchers were supposed to get 20-year leases and they end up with nothing. That's not a middle ground.

Now they're scrambling to figure out how to mitigate against wildfires. The park is talking about using all the practices they disallowed—mowing, beef cows on the ranches. But they're still evicting people out of their houses.

I’ve documented that over 130 houses have been destroyed over the last 50 years in Point Reyes National Seashore and GGRA by the Park Service, and they're about to destroy another 50.

A study found that we need 1,000 affordable housing units in West Marin, yet at the same time, the county and the state have put over 1,000 units into short-term rentals, so no one can afford to live and work here. Over 80% of the workforce commutes in. It's just not sustainable.

It's devastated our community. We lost 35% of school-age children over the last decade, 41% of our high school students. We're about to lose another quarter, at least, of our students.

We're just on the verge of collapse. These actions are putting a stake in the heart of our community. We need to work together to salvage what we have and be able to start building again.

Why is the Park Service doing this?

I can't talk to their motivation.

Has there been any evidence from any of these studies that there's any environmental damage to the park from these ranchers and farms?

No. I think that the farms are actually an asset to the park and to the environment. We've shown that we live in harmony with nature, not adversely; and farms, which have been there over 150 years, have been the thing that actually kept nature intact in a form that the public can enjoy.

There are studies that show that grazing is essential to not only promoting native plants and wildlife, but also endangered species, like red-legged frog.

There's a disconnect. We need to get back together and work together on this because we're going the wrong direction.

Have there been any help from California state politicians or any representatives, Marin County politicians? Have any political representatives sided with the farmers or tried to help them?

No.

Do you think the message Marin County is sending is this is a place for billionaires and the wealthy, and agriculture isn't welcome here?

It becomes a playground for the rich.

I think that's something that in history is not going to be looked at as a positive step. It makes me very sad that this is the direction we're going.

Do you think this is an isolated incident from the National Park Service? Or are you seeing evidence of a pattern in government against production, agriculture and grazing on our public land?

This is not isolated. This is happening all over the country.

Veganism as a solution to climate change is not accurate or real. We're now going back to a understanding that livestock and animals and dairy products are really essential and cows are a part of the solution.

What can you say about the farmers’ gag order? I know you can't speak for them, but what have you observed?

Mediation should last maybe a week or two. This has been three years. So they just kind of wore the ranchers and dairymen out.

They were threatened by different people that there were repercussions if they did talk and so they were scared.

What kind of repercussions?

I can't talk to that but I assume it was severe enough that people were afraid to talk.

Did the public have any input in this process?

The community was unaware of what was going on and shocked when this announcement was made a couple weeks ago.

When we had a whole public process it showed 20-year leases were in balance with environmental needs. It was going to be a positive thing for the community.

Now we have businesses, schools, churches are all going to be, if not closed, greatly diminished in our community. The very thing that the public wants to see is going to be gone.

But what would you say to folks who say this is voluntary, this is what the farmers and ranchers want?

I think that's the narrative that the Park Service wants on this, and the Nature Conservancy.

The farmers didn't want to leave their home of many generations. They didn't want to leave their businesses. But not having a landlord that was really there working with them was not sustainable.

The settlement has not been made public, but did they get enough to relocate?

No. They got enough money to maybe buy a house in the city, or part of a house. There are multiple members of these families, any settlement was split up between multiple people. It wasn't that much money at the end and not enough to buy another farm or to at lease another farm and move to another place. This is not a good settlement and it's not a good indicator of how we're supporting our farms and our communities.

It seems there was suddenly a big push in January 2025 to get this done, what does that say to you about maybe some pressure to wrap this up before a new administration came in?

I think it was very obvious that that's what the intent was, to get it done before the new administration got in.

Did that play into some of the pressure that you said that they experienced, not just to stay quiet, but also to sign by a certain date?

The simple answer is yes.

So what's next for these ranchers? Is there any hope for them? Now that we're informed, people are angry. The response even online has been overwhelming. This does not seem to be what the public wants. What options do these farmers and ranchers have?

We're looking at multiple approaches. One is to see if the administration will reverse this decision. The other is, there's a couple lawsuits still in play. The third is to create public awareness to support these farms.

And the fourth is, we're looking with intention at how we can relocate these dairies and ranches within our community so we're not losing our community as well. That's going to take time and money. We're not afforded time with this settlement. We have six to nine months essentially to move the dairies, and that's not enough time to find a defunct dairy that we need to fix up. That all takes time and money.

And so I am asking and urging the Nature Conservancy to give more time for these ranchers and dairies to move, just make it impossible to relocate, keep them going in production.

And then we need to raise money. I figure for all 12 of these ranches and dairies to be relocated, probably $80 to $100 million. It's $5 to $10 million per dairy. For the beef ranches, land's not cheap.

The Nature Conservancy is talking about bringing in grazing contractors. Spending all this money and effort to move these local food sources only to be replaced by grazing contractors—what is the logic here?

I think it's very short-sighted and not really understanding what it takes to farm and produce food. I think they're only trying to mitigate wildfires, and they don’t have experience of how to do that.

It's interesting that this is happening right now because the world is changing. We are starting to appreciate animal products in our diet; the importance of grazing in the wake of these L.A. fires. So this approach feels outdated, like a relic of a mindset that we've grown out of, but we can't reverse it. Once they're gone, they're gone forever.

It's going to be very hard to reverse this whole trend.

As I said before, we have county, state, and federal parks that are taking animals off millions of acres, and we have wildfires every year. I advocated for using livestock in Sonoma and Marin County 7-plus years ago. A Sonoma County committee showed that cattle grazing can be an income source while at the same time mitigating wildfires and producing food. Whereas these contracts of sheep and goats can do about 5% of what's needed and cost millions of dollars for taxpayers.

Yes, we have climate change, but we have to manage differently. Climate change is not a reason not to look at how we manage our lands, how we produce our food, and how we can do both at the same time and really make it positive and work in harmony with nature.

We can all work together to make a better future. We need to do a better job of educating the public about where their food comes from, how it's farmed, and that it's so important that we have this resource here in Marin and Sonoma counties.

And actually, we're not unique to everywhere around the country and around the world. Local farming and food systems are endangered everywhere.

How do we work together to make that change? The path we're going down is not working. We see more climate changes. We have more extreme weathers. Let's work together on the solutions.

So I think there's ways we can address climate change and use farms as a solution.

I've converted our vehicles to electric on my farm. I have a methane digester where we capture the manure from the cows and produce all electricity for the farm and the electric vehicles. We have a truck that feeds the cows that's powered by the cow's waste. I have an electric loader. I have an electric skid steer. I’ve driven electric cars for over 20 years. We did the first commercial trial in the United States for feeding red seaweed to cows. Feeding a quarter pound of this one variety of red seaweed in a 45 pound diet, you can get ta 95% reduction in enteric methane, which is the belches from the cows.

We were the first dairy to have a carbon farm plan by adding compost to the land, using animals to rotational graze. You're building organic matter and soil, which grows more grasses and more crops, that pulls carbon from the atmosphere and puts it back in the soil through photosynthesis. And it's being recognized internationally as one of the only ways to reverse climate change, rather than reduce it, by pulling carbon from the atmosphere and putting it back in the soil.

And so my assertion is livestock has an essential role in reversing climate change. I think these practices are all essential to a farming and food system that is a benefit to the planet and our community.

What a tragedy to lose 12 examples of this. For the ranchers to stay if that were even an option, I'm sure they wouldn't really want to stay unless they know that their landlord is behind them. So it seems like we need to start calling for change at the National Park Service. It would be amazing if the public could start to change its perspective of these shared public lands.

I agree, and I think that we need to share these practices, this viewpoint, and this opportunity that we have to the greater public and our consumers and our legislators.

We need to kind of all be working together. We need leadership that really helps us see this vision and this future working together with us.

If people want to help get involved, what can they do right now?

We're developing that, but I think that we'll be reaching out to the new administration, the new Secretary of Interior who oversees the Park Service, to ask for a change in direction. And exactly what you said, how do we look at these as opportunities and a different vision of how the Park Service works?

Yeah, for a growing population that needs to be more self-sustaining and continue to feed ourselves from farms like yours, with leadership led by farmers and ranchers who understand really what's at stake and how to do it right.

I think the other challenge is farmers are getting older. The average age is 60 years old. There's like 1% of the population that's feeding everybody. We don't have a next generation unless we really deal with intention. We need to address issues urgently and really look to the future. So thank you.

Share this post