EXCLUSIVE: Ecologist Proves Grazing on Point Reyes Is Crucial to Biodiversity & Native Plants

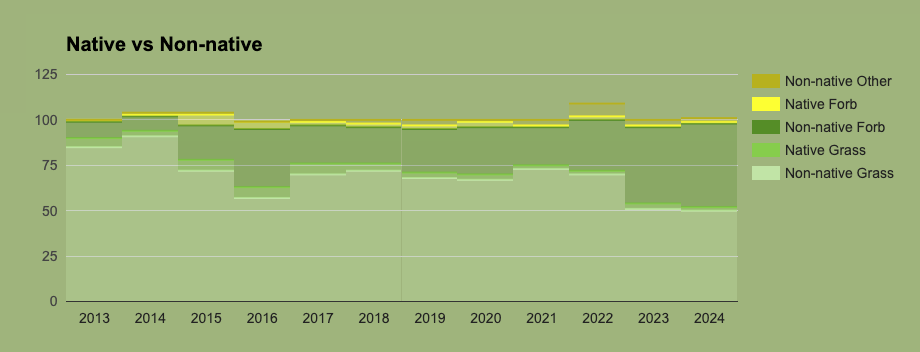

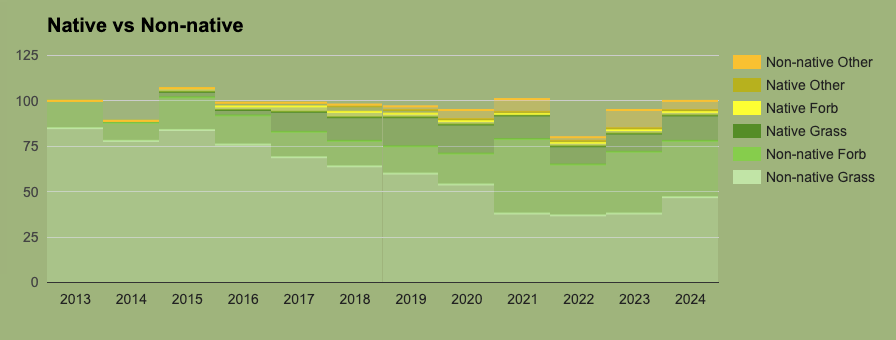

And Nate Chisholm has the data to prove it. In six years, his grazing operations saw a 101% increase in plant biodiversity, and a 61% increase in native plant cover.

Grazing ecologist Nate Chisholm of Project Savanna has a decade of data showing how cattle grazing improves biodiversity and native plant growth in Marin and Sonoma counties. His studies were conducted near Point Reyes National Seashore, where 12 ranches are being evicted. The National Park Service has not expressed interest in his research.

“Over the course of about six years, we increased the number of species on those 10 by 10 meter plots by 101% on average,” he says of his grazing program. “So if there was 15 plant species in that plot at the beginning, there was 30 at the end on average. The percentage of native cover also went up by 61%. So even as there was more species, a greater proportion of the ground was being covered by native species than by non-native species.”

Chisholm, a grazing ecologist and rancher now based in Kenya where he is studying the impact of megafauna on savanna ecosystems, says his results show a positive and dramatic impact on biodiversity and native plant cover in environments very similar to Point Reyes.

Examples of Grassland Monitoring Points

Chisholm points to three plots with similar conditions to Point Reyes—a wet coastal microclimate with lots of perennial grasses.

“We took 10 meter by 10 meter plots on these ranches, and we had a professional botanist come and, every year at the right time of year, count all the different plant species and categorize them,” Chisholm explains.

Each shows a dramatic drop in non-native invasive grass dominance and a proliferation of diverse native plants.

Chisholm explains this is because, on rangeland ecosystems, the grass needs animals to cycle the nutrients, take away dead leaves, and plant their seeds. “For pretty much the most basic functions of a plant, they rely on herbivores to provide those functions.”

He likens it to hydroseeding a lawn—without raking to expose bare ground, it’s uselss. “If you just go to your lawn right now and throw seed in there, you might as well throw the money out there, it’s not going to do anything.”

For areas below 10 acres, the highest plant biodiversity on earth can be found in Central and Eastern Europe, on pastures and hayfields where managed grazing has been present for thousands of years. Point Reyes could have been an opportunity to further research grazing and biodiversity.

“It was such an opportunity for conservation and ranching to work together, because all the tools were right there,” Chisholm says. “We’ve destroyed that opportunity. It’s an unfortunate situation.”

Grazing has a ripple effect on pollinators, ground-nesting birds, soil health, water retention. According to hydrological tables, tall grass sucks out moisture from the ground four times faster than grazed pastures, which conserve water much more effectively.

Is the Park Service Interested in the Data on Grazing?

Before leasing land for his own operations, Chisholm worked on ranches on Point Reyes. He says even back then it was clear the Park Service was opposed to the ranchers and to grazing.

“I think everybody knew that the Park Service was not interested in hearing data,” he says. His studies, including photos and detailed documentation of biodiversity trends, remains publicly available at the Sonoma Mountain Institute website.

For a preview of what Point Reyes will look like when the ranchers are gone, Chisholm says we should simply run his data in reverse.

“Eventually it’ll be velvet grass and coyote bush.”

When this occurs, there will be no accountability. Unlike a private rancher, Chisholm says, the National Park Service does not answer to anyone—or suffer the natural consequences of poor management.

“When a conservation entity, whether it’s a government or an NGO, takes over—if they don’t do a good job, if they don’t achieve their biodiversity outcomes, what happens? Where is the accountability on that?”

He adds that the tule elk herds that have grown on Point Reyes rely on cattle, too.

“Elk are just as reliant on larger grazing animals as the plants are. They cannot deal with this velvet grass that’s three feet high. They just can’t eat that.”

Chisholm believes it is inhumane to leave smaller grazers to deal with the large invasive grasses alone. “That’s not how elk were ever meant to graze, they follow behind larger animals.”

Grassland Ecosystems Thrive with Managed Grazing

“I am in this to do stuff for the plants, and the domestic animals will help you create natural conditions better than the wild animals on the vast, vast majority of landscapes because you can manage them.”

Ranchers often grow to appreciate and understand grassland through their animal management, but Chisholm’s road to cattle management began with a passion for plants.

Since middle school, Chisholm has focused his education and career on conserving grassland savanna ecosystems.

“I’m a rancher but I came to it through ecosystem restoration and native grasses,” he says. “Starting with the grass, I grew to love the animal part of it too. I came to it totally from a biodiversity perspective. I really do think the data shows that managing livestock well can increase plant biodiversity.”

He believes the response to a beautiful, managed pasture is innate.

“To me, National Parks are to nourish the human spirit and to conserve biodiversity. This broke multi-generational families and moved us farther away from the Park’s directives and mission.”

Can the evictions be undone? Is anyone in the present administration willing to look at the data?

Gee, I remember not that long ago we were chided to “listen to the science.”

More’s the pity.

Allan Savory, Khory Hancock in Australia, and many other scientifically-minded ecologists are utilizing grazing animals to do things like restore grassland biodiversity, reverse desertification, and improve soil life. It's a proven science that can only be done with proper management by humans. Letting nature "re-wild" is one of the slowest recovery methods that ultimately can lead to loss of biodiversity altogether, which is what these "environmentalists" fail to see.

It's a shame that the Parks service in California is run by politics more than actual evidence. I'm expecting to see more of this in the future. Hopefully, grassroots journalists and methods like regenerative agriculture/permaculture can shift the narrative into something that makes more sense. The old guard belief of blaming grazing animals needs to be rethought. It's just being co-opted right now by people with too much money that keep wanting to make more.