Hippies & Cowboys: The Murder of Mendocino County Rancher Dick Drewry

When 85 year-old rancher Richard Drewry was killed, I shot an investigative documentary about his case and the changes in my hometown. Nothing could have prepared me for what I saw.

This article is a companion piece to the short documentary “High Country Murder.” Stream the 20-minute film at Real Clear Politics or below:

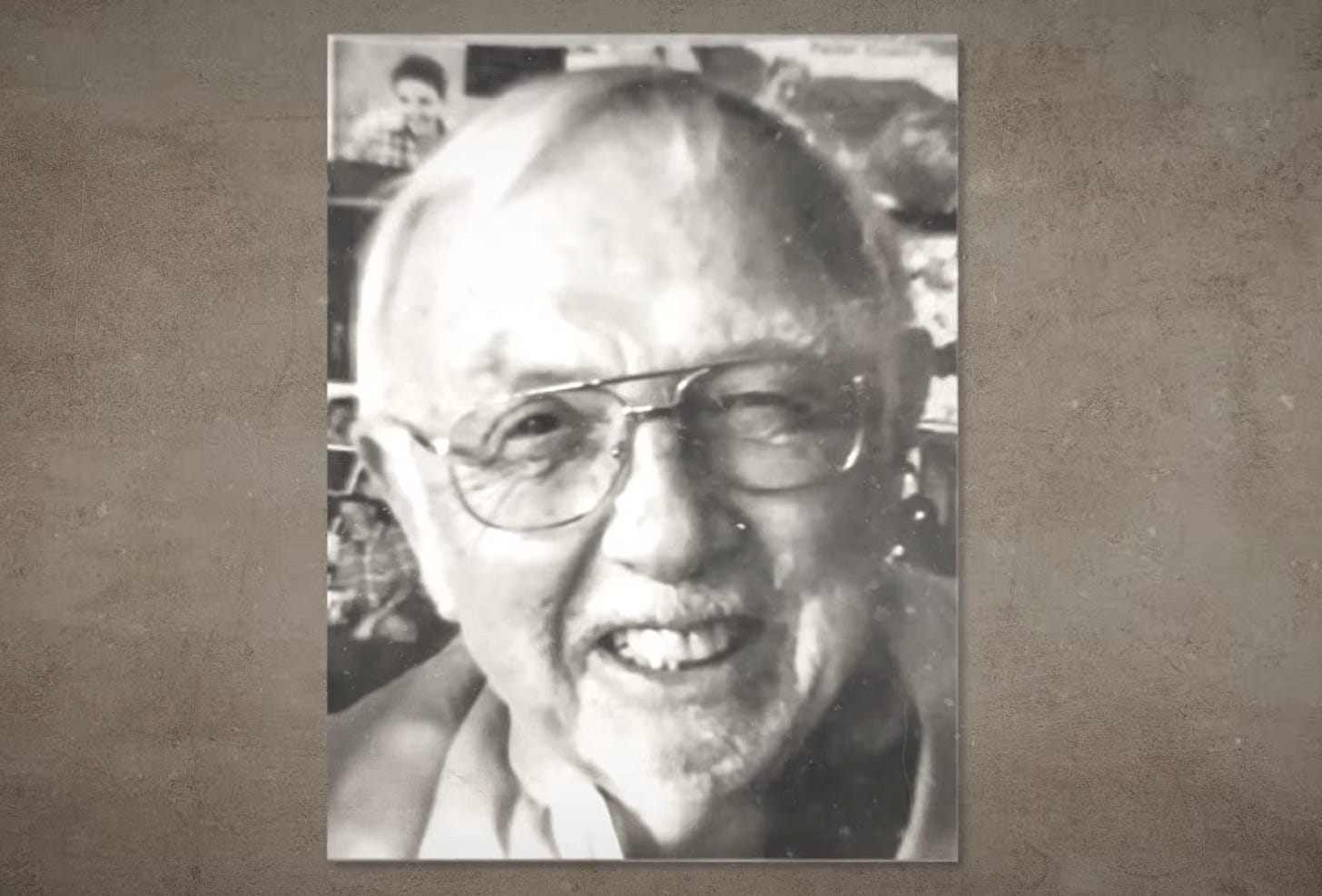

Richard “Dick” Grayson Drewry was a cattle rancher who lived in Humboldt County, California. He was 85 years old when he was found murdered execution-style outside the home his pioneer grandparents built.

On the morning of January 26, 2021, his still-running blue Ford Explorer was found on a remote stretch of Bell Springs Road. Dick was slumped over the steering wheel, a single gunshot wound to the head, blood still dripping in the wet cold hours before a heavy snowfall.

His murder is unsolved.

The Hippies & Cowboys of Mendocino County

I was living 500 miles away when I heard about Dick’s death.

My father is the ranch veterinarian for Lake, Humboldt, and Mendocino counties. He drives two hours in any given direction for his ranch calls, in a Dodge Ram pickup truck with a refrigerated vet pack in the bed. I grew up going to work with him. I’d help move cows or hold horses. It was always nice to have the vet’s kids around—extra hands eager to help at zero dollars per hour.

Many of his clients are ranchers like Dick Drewry; old school with a blue heeler in the truck bed and a gun on the dash. Tough, keen, sharp, self-deprecating. They can tell if a blacktail deer on a distant ridge is legal, they know which parts of the forest to avoid. Over the decades, as the world around them changed, they quietly figured out new ways to navigate the mountains.

Others are back-to-the-landers, or “hippies” as outsiders might call them. Generous and friendly, these are the diehard flower children. They would give us homemade bread, fresh goat’s milk, strawberries from the garden. If the garden had a little fenced-off patch, that’s just another herb. They warned us about processed food and plastic long before such cautions were in vogue on Instagram.

Some of his clients are outlaw growers who came here after the back-to-the-landers changed the culture of the North Coast and legalized cannabis in the “Emerald Triangle” of Humboldt, Mendocino, and Trinity counties. They were friendly, too. They lived in remote mountain hollows on places like Spy Rock Road, down long rough private driveways. Sometimes we’d come up to a gate, and big men in camo with AR-15s would boil out of the woods to open it for us. They’d give me a nod in the passenger seat. The ranch vet was one of the few outsiders allowed.

To my dad, a father of eight and an elder at the little Bible church in Potter Valley, everyone he meets is a child of God. Growing up poor in the flat and dusty Central Valley, moving to a place as beautiful and wild as this makes him feel like a rich man.

He likes all his clients, sees the humanity in everyone, from the Hollywood motorcycle stunt rider covered in burns from a serious accident who now operates an enormous black market weed operation guarded by pet wolves, to the 80 year-old cowgirl named Billie who saddled up for every gathering and branding at the John Ford Ranch until the day she died.

Billie Drewry was Dick Drewry’s sister-in-law. I never met him, but there are a lot of Drewrys. They are one of our founding pioneer families.

In 2021 I was living in sunny Southern California, working in film, learning to surf. My childhood felt far away. The news of Dick’s death brought me back.

In some of these isolated hollows, you might not know many folks outside your “neighborwoods” even on the same mountain. Like Appalachia, the geography lends itself to outlaw enterprise. You could grow something or brew something in your backyard and no one would find it. There is a sinister and smothering quality to the dense forests and layered hills and it often intimidates outsiders. Fog rolls in from the Pacific Ocean, the giant redwoods and mossy oaks create a shadow world. You can’t see in front of you, you don’t know what’s down the next hill or through the next patch of trees. Anyone could be there, anything. This is where the Bigfoot myth was born. It’s logical to believe something supernatural lurks here.

For years we all saw and felt a dark new presence, but I told myself it would stay in the shadows. The sanguine coexistence of the hippies and the cowboys and the outlaws would go on. We would keep our common ground, overlook the rest.

Dick Drewry’s murder disturbed that illusion. It seemed our world had collided with something new, something I had never encountered face-to-face in all my years growing up in Mendocino County.

Cartels in California

“It sure looks like a hit to me.”

On a rainy day in Eureka, where rain is its most oppressive and gray, I was in the Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office with my sister Michaela and a film crew—Ryan Francis, cinematographer and editor, and producer Graham Kelley.

It was 2024, three years since the murder, with no answers to the questions I asked anyone who would listen. Picturing my father in his pickup hours outside of cell phone service, I’d check local news websites, call friends and ask for updates, even the latest rumors. I reached out to the local FBI office, hoping to clarify the whispers I kept hearing about cartels and organized crime moving in, infesting themselves deeper in the remote mountains, getting bolder, more aggressive. Then I was accepted to the Palladium Pictures documentary film incubator in Washington, D.C., the chance to make a short film. I went home with a camera crew to look into Dick’s murder. Whatever we found out, there would be a story.

“It has all the Hollywood makings of a hit,” Sheriff William Honsal is saying. We’re looking at pictures of the crime scene: the pitiful Explorer in the snow, driver’s side window rolled down.

Sheriff Honsal is about 6 foot 4, well spoken. He made time for an interview that day after a taxing weekend dealing with a pro-Gaza protest at Humboldt State University. I know he has rubbed some locals wrong because of his outspoken political views. I’ve also noticed that all the peace-and-love hippie towns around here have started hiring real hardass conservative sheriffs.

Honsal is echoing the predominant rumor in town. Most locals I’ve spoken to believe Dick Drewry was killed by some member of foreign organized crime. Some say he shot a dog who was harassing his cattle, and the dog belonged to a Bulgarian crime boss who put a hit on Dick’s life.

“Once people started recognizing that there's money to be made in marijuana, and it all has to do with scale, it just blew up up here,” Honsal says. “Then we started seeing the organized crime move in.”

I’ve had friends ordered to turn around and leave by men with guns while hiking on public land. While hunting or horseback riding, I have stumbled into large-scale grow operations complete with elaborate drip systems ripping water from the Eel River watershed, fragrant with chemical pesticides and fertilizers.

“We've seen Bulgarians, Russians, the Chinese moving in and trying to take over the illegal industry here,” Honsal says, “It's not just marijuana. We’ve seen our homicide rate go sky high, as well as human trafficking, labor trafficking, sex trafficking. You look at this and go, this has got to be a third world country. No, this is Northern California, this is what's going on.”

Old Timers and the Green Gold Rush

Katie Delbar is a rancher in Potter Valley. I’ve known her since I was born. I grew up with her daughter, Kayla, a good friend.

“I never heard him say an ill word about anyone, he was just a kind, kind person.” We’re sitting at the big kitchen table in her dining room. She shows me photos of her dad, Jim Eddie, with Dick Drewry.

Jim is 89 now. Talking about his friend’s death pains him.

“It’s sad as hell.” Like Dick, Jim has been a rancher all his life. “If I had money, I’d put a reward out but it’d have to be big enough to get people to talk and I can’t do that.”

I ask if things have gotten worse in town.

“This is a different group of people here now,” says Katie. “People in the 60s who grew illegally were different. Now we have people from all over the country, all over the world, you hear 3-4 languages when you go to town. They’re here for one reason: To make money.”

We look at a photo in one of the photo books of a group of boys on their bikes.

“This is the crew,” Jim smiles. He looks at it for awhile in silence. “They’re all gone,” he says, “Except myself.”

6000 Illegal Grows on American Public Land

We are doing our best to follow Katie on a sketchy logging road to one of her grazing leases in the national forest. She is hauling a horse trailer, driving up the mountain like her rig has sport mode.

There are an estimated 6000 illicit marijuana grow sites on American public land, all over the West—California, Montana, Idaho, Oregon, Colorado, Washington. The porous Southern border provides a constant labor stream.

“Even on the East Coast, everyone knows where Mendocino and Humboldt Counties are. They don’t have any idea what happens if that becomes your neighbor. Not only where you live, but in the national forest.”

Katie has been riding through these mountains pushing cows all her life. She’s a consummate cowgirl. The environmental damage left by these grows distresses her. “All the plastic, insecticides, and pesticides. The deer, the bear, all the animals are dead.”

Michaela rides her paint horse, Blue, up ahead with Katie and Kayla. Ryan, Graham, and I hike in on foot, lugging equipment. The deeper we get into the woods, the more unsure I am about this idea.

We arrive at the grow site, and I get the mother of all bad feelings. There is junk everywhere; propane tanks and decrepit campers and piles of odds and ends. I spot children’s toys and Christmas decorations, an old stove and a busted washer and dryer. Most disturbing of all: Set neatly beside the trail is a backpack with a fresh pillow on top. It had rained the night before, but the pillow is dry.

We grab some shots and get out of there.

Lawman in the Emerald

“For years and years, everybody here said, ‘Yeah, it’s illegal, it’s just a little more legal here.’”

Mendocino County Sheriff Matt Kendall has found workers at grow sites who don’t know where they are. They believe they are in Washington, or Oregon. Many don’t speak English. They’re forced to work by the cartel, who gets them across the border and then puts them into forced labor on grow sites. Many have family back in their home countries who the cartel has threatened to kill if their loved one does not work.

“Sometimes ranching and pot growing are in competition,” Kendall says. “Fences have been cut, some of the water sources are being developed to provide water to marijuana. Cattle are shot to feed people in these grow sites. We’ve got some bad folks in competition for water, in competition for land.”

Tests show that much of the cannabis sold in legal dispensaries comes from black market grows. He says people should think of the current cannabis supply the way they thought of diamonds after the Leonardo di Caprio movie came out in the 90s.

“Blood cannabis.”

Tribal Towns Caught in the Crossfire

We meet Sheriff Kendall off Highway 101. Ryan and Graham are driving their windowless grip van. The first thing he says is, “That van is going to have phones ringing across the valley the second we hit town.”

He tells us to stay close as we head into Round Valley. I get in the passenger seat of his truck, next to a Bible and a patrol rifle. Country music plays on the radio.

Covelo is a tribal community deep in the Mendocino County mountains. It has a dark history: Here, local tribes were rounded up and forced to march in a West Coast Trail of Tears. Because I am a child of these mountains, I believe in things that modern, sophisticated people may not. I believe, for example, that places have memory. In this place the trauma is palpable, heavy and poisonous in the air of Round Valley like sickness in the blood.

Covelo is one of the most beautiful places I’ve ever seen. Long green valleys roll into purple hills. Live oaks, hay fields dotted with round bales. This town should be paradise. Instead it is covered in junk, old cars, rotted-out mobile homes, hoop houses row on row.

“It was really clean when I was young,” Kendall grew up in Round Valley. “There was a lot of business, a lot of industry here. This would never have happened if we still had good, sound, solid jobs.”

Foreign criminal organizations have entrenched their presence deep across the valley. Safe from local jurisdiction, they found pockets of land ripe for the taking. I had heard told stories about cartel members dating young Native women to steal their land rights, stories about packs of wild dogs let loose after harvest to terrorize locals and their cattle. One rancher up at Lone Pine told me all his cattle had torn ears.

“The Silk Road has been paved into Mendocino County with the illegal drug trade,” Kendall says. “We’re not far away from the things we saw in Mexico during the narco wars. We’re not far away from heads in the square, intimidation of entire populations, addictions of entire populations. I don’t know how in the hell we’re going to hit the reverse gear and back our way out of it.”

Driving through town, a man in a black ski mask in a lifted Dodge dually passes us, hauling massive water tanks. It’s planting time, and the valley is buzzing.

I ask the sheriff if he ever gets any help from the state. He says no, Gavin Newsom has never returned his phone calls.

We pull over at the back of the valley. Ryan flies his drone over several grow sites. All of a sudden, a pickup truck roars down the main road across from us. Cool as ice, Kendall tells us to get back and waits by the truck with his patrol rifle until he is satisfied the driver doesn’t plan on a confrontation.

“It was a strange thing in Mendocino County not to know your neighbors 20 years ago,” he says as we drive on. “But people don’t know their neighbors anymore.”

On our way out of the valley a few hours later, he asks me if I had noticed the car following us all day. I never did.

Going Back to the Land

Bell Springs Road is an old stagecoach route, bad and rugged, winding its way north from Laytonville to Garberville.

We’re on the Laytonville side at Happy Day Farms, across the mountain from where Dick was killed. Brothers Lido and Casey Oneill feed half of Laytonville. They raise vegetables, pigs, sheep, and cannabis.

Their parents came here during the first wave of the back-to-the-land movement in the 1970s. After San Francisco’s Summer of Love, they were part of that searching post-war generation looking to recreate the American dream in their own image.

North of San Francisco, they found paradise: land beautiful and virtually empty, just a few loggers and cowboys. Property was plentiful and cheap. It was a chance to get back to nature, away from the plastic promise of 1950s suburbia.

Casey and Lido are rugged, capable, warm. They have a large Black Lives Matter sign outside the farm stand and a menagerie of hapless dogs. Lido is a former firefighter for CalFire, Casey articulates his policy views with the nuance of a career politician, neither of them look like guys you would want to face in a bar fight. They are true farmers. They care about every plant, every animal. At the roadside farm stand, they sell bone broth and kombucha and produce and gluten-free chocolate chip cookies.

The original Oneills bought this land, a piece of the old Drewry ranch. They only grew a few cannabis plants for themselves and their neighbors at first, the brothers tell me.

“In ‘85 they got busted,” Casey says. “National Guard, helicopter, all for 30 plants. That was real formative for us. Especially for Ma, it was an incredibly traumatic event that she never got over.”

I don’t ask the brothers, so I don’t know about them. I do know that many of the back-to-the-land families that came here with humble ambitions wound up making tens of millions of dollars selling cannabis on the black market.

Casey says he was busted again in 2008 after coming home from college. “Did some jail time in 2009, then I got really into the local food movement.”

The fallout of legalization, a process the brothers have gone through for their private cannabis label, frustrated him.

“If you can grow an herb for decades in an unregulated or semi-regulated environment and then all of a sudden the government’s like, the rules have changed and now they’re this long”—he makes a gesture like unrolling a scroll—“What are people gonna do? It’s still food on the table. People have a right to grow plants, people have a right to grow herb.”

He caveats that not everyone has acted responsibly. “When you see violence involved, when you see environmental degradation involved, that’s a different story. But when it’s just cannabis, you know I don’t think it should be a felony. I don’t think it should be a misdemeanor. Legalization lowered the penalties, but the price went down, and it made it less attractive to be involved. At this point you still see mom-and-pop small scale production but you also see really large-scale, kind of unregulated criminal element production. That was always happening. Now it’s on a bigger scale. The black market is still thriving because the tax rate is so high.”

I ask if they have seen more organized crime since legalization, and if the climate on Bell Springs Road has gotten more dangerous. They brush this off. Like everyone else out here, they don’t believe or don’t want to believe that they are in any danger. It would be hard to live here if you were afraid.

“It all depends on your neighborwoods,” Casey says. He blames the government for whatever violence there is. “Doesn’t mean the people who do violence are off the hook but the conditions for violence are 100% the result of bad governance.”

With our cameras rolling, a truck hauling equipment pulls up and stops outside the farm stand. “Can I have your autograph?” the driver shouts, and the brothers laugh.

He wants a grapefruit kombucha. “What do I owe you?”

Casey says don’t worry about it, thanks him for some favor.

“Get outta here ya hillbillies,” the man chortles.

“Love ya buddy.”

Throughout our interview, the brothers wave at every vehicle that passes. They know everyone in their neighborwoods, but they say they don’t know what happened to Dick Drewry across the mountain. The case unsettled them. Lido had a camera on that side of Bell Springs Road, but he says it was off that day because of the snow.

“I think the ranchers have it the hardest because they’re managing large tracks of land in which there are trespass grows and you are dealing with a criminal element and weapons,” Casey says. “One of the neighbors moved out, tired of having to deal with that for his cattle. I feel for the ranchers. We run just real small pasture, but if you had to factor into your animal raising paradigm that that somebody might shoot my animals, somebody might shoot me, that’s hard to deal with. If you live out here, you gotta be…”

He trails off. Lido picks up his thought.

“You gotta be self-sufficient in all ways. Because law enforcement’s a long ways away from us. That’s for sure.”

The Last of the Wild West

Through all my feral childhood in these hills, I’d never been to or heard of Rodeo Valley. We pull up and I am struck again by the vastness of Mendocino County. Here I am, still surprised by its beauty, discovering a new facet of it. I feel a wave of homesickness. I love Mendocino from the bottom of my heart. It’s the only place I ever feel right. In that moment, I resent my life back in Orange County. I feel uprooted, a house divided.

Dan Moore is married to my friend Kayla Delbar, now the ag teacher at our high school, another generation of her family keeping the town together, the center that holds. To me, she is the heart of this place. Dan is a full-time cowboy.

I’ve known Dan since we were kids, too. My neighbors in Orange County would not believe he exists. He is in short what an old timer might call—the highest compliment it is possible to give—“the real deal.” He doesn’t wear a cowboy hat for Instagram and I doubt he watches Yellowstone. He is my age but seems ageless, like he grew out of the ground organic as the oaks. Pulling up to our truck on his stocky bay quarter horse, if you watched this moment in black-and-white it could be 1880. There is no perceptible difference between him and those pioneer explorers whose blood runs in his veins.

Dan was Dick Drewry’s nephew.

“They kind of felt like things had eased up,” Dan was saying. He is moving cows to summer pasture all that week in Rodeo Valley. It had been a long day. He and Dan Arkelian are sitting on the back porch of the old bunkhouse. “When my brother and his wife found Dick’s body, it was kind of a step back for all of us. You know, like maybe things aren’t getting a little better. Maybe they’re actually getting worse.”

Dan Arkelian is another old friend, the foreman at John Ford Ranch. Dick Drewry’s death angered him. “How could a guy live there 80-some years and then have an end like that?”

I asked what he is seeing out in these mountains, how things have changed.

“You didn’t really see any cartel before. You’d see signs in the roads, or they’d leave clothes. The cows quit going places. You just figured there’s places you didn’t go. Even here, there are gardens all over, and this is private property.”

Dan Moore grew up about an hour north of his uncle’s ranch on the same ridgeline. He gives me a set of classic rancher directions; I nod like I follow. “Myers Flat; Mail Ridge starts right there north of Laytonville at the old white house, runs to the forks of the river north of Weott, on the old stagecoach route. Further north you get the more tame it becomes. Go south it gets pretty western pretty fast.”

“What was it like growing up there?”

“You drove pretty slow, minded your manners.” Dan is nonplussed, like he’s discussing the downsides of taking the toll road on his Irvine commute. “Pretty much loaded a pistol when you got off the blacktop.”

I ask if he believes the rumors about his uncle being killed by the cartel.

His answer surprises me. He says no.

“It’s probably somebody that was pretty close to him.”

Culture of Silence

No one will talk to me.

I’m sitting in the passenger seat of my truck outside the Ridgetop Cafe in Fernbridge, a half eaten breakfast burrito on the console, and all the folks I’m supposed to be interviewing in a couple hours are canceling on me. Dead end after dead end. Suddenly, no one wants to talk.

We were about to head up to the Drewry ranch on the north side of Bell Springs Road, where I have interviews scheduled. It’s our last day of filming, and I’m out of leads.

Dan’s gut feeling he shared in Rodeo Valley fits what I am hearing from my sources. The closer I get to where the murder took place, the more people seem to know. Even the Oneill brothers on the south side of Bell Springs have no idea what happened. It’s like the forest kept the secrets close, and the truth from getting out.

I was hearing rumors about water, and a neighbor. This neighbor, according to the rumors, was in his 70s. He was originally from Berkeley but came here to Humboldt to grow weed. The rumor was, he had reached a water agreement with Dick Drewry. Then Dick, who neighbors told me was very opposed to cannabis, found out that his neighbor was using the water to grow. He ended their agreement.

One source said this neighbor may have been trying to go legal, following those onerous regulations laid out by the state of California so he could be a legitimate operation. But he needed a water source to do that, and Dick Drewry cut him off.

And so, the story went, he stewed on this for a couple years, blamed Dick Drewry for everything going wrong in his life.

Then one morning, people tell me he came home and announced to his daughter and his son-in-law, “I shot that motherfucker.” Then he went back to his trailer.

I have heard various parts of this rumor over and over again, in bits and pieces, until this story has taken shape.

But the one thing no one wants to give me is a name.

Scene of the Crime: Bell Springs Road

Dick Drewry was killed in a lonesome place.

To my left, whiteface cows graze in the near distance. Then the valley dips low and sweeps up into heavily wooded foothills beneath a universe of purple mountains. To my right, the green hillside rises steep. At its base there is a homemade wooden sign wearing Dick’s name and the Drewry ranch brand. A set of blacktail antlers hangs off this sign—a North Coast tribute.

I don’t know a soul out here, and for as long as we are posted up getting drone footage and shots of the crime scene, I only see a few cars. Each driver is alone, each looks at us intensely.

Only one stops. An elderly man in a beat-up Toyota. He rolls down his window.

“What are you all doing up here?” he asks me.

We are conspicuous with our drone, our grip van, our radio headsets. If in fact Dick Drewry was killed by a neighbor, I don’t know what that neighbor looks like. I watch the elderly man in his truck disappear down the road. I don’t breathe easy until we are back in Garberville.

Small Town Rumors

All I’ve got are rumors. Everyone is scared to talk.

I heard that after the murder, that neighbor was arrested for assaulting his son-in-law. Someone else told me he beat his son-in-law with a metal pipe after he went to the police and told them what he knew about the murder.

The police neither confirm or deny anything. They tell me they have a person of interest, and that the DA doesn’t think they have enough to make an arrest, and that they need more witnesses to come forward and tell police what they know. That’s all they will say.

I searched local property records on Bell Springs Road near the Drewry Ranch. I searched for relatives and family trees. After many hours of digging, I came across a woman’s profile on Facebook. Her name fit.

She shared photos of weed, antiques, dogs, and a landscape that looked familiar. She posted a lot, and her posts were public. Her posts were sort of stream-of-consciousness. I read, and read, and kept reading. I got the sense that she was a good person, a person searching. She alluded to childhood pain and attempts to reconcile with a father she barely knew, a man she came to live with, along with her partner, in a remote part of Humboldt County. Now, she says, they no longer talk. She lives in a different state.

I kept scrolling. I scrolled back years. Back to 2021.

She talked about the neighbor’s cows getting out and into their garden. She talked about fear, and “getting away from the bad guy.” She posted about criminals and guns and bad dreams. In one post she wrote, “I would do a lot of selfless acts, but one I would never do is take the blame for a crime I didn’t commit.” In another she asked Facebook, “Where do they put people who are old and have dementia that killed someone and kind of violent?”

And then, there it was:

“Been staying at a hotel with my man, my son, and my dog, had to leave by dad’s because he has been getting increasingly violent over time…last year, he killed our neighbor, and felt no remorse at all…nobody knew it was him…they suspected it was him, but were not sure…he put us all in a bad situation…and he was getting more scary every day…was a loose cannon…didn’t know what he was going to do next…so we decided that no inheritance is worth the kind of stress this involved, and went to the police because he kept saying that he should kill the rest of the guy’s family…he shot the guy while he was sitting in his car, and people in the community were scared, my dad hasn’t been arrested yet, but they are testing the evidence they have, but might be arresting him sooner for assaulting my man…just needed to let people know”

Putting Together the Pieces

Dick Drewry was 85 years old when he was murdered. That morning in January, a snowstorm was coming. He drove down his long driveway and turned onto Bell Springs Road, where for some reason he pulled over. His wife Phyllis was always with him, but she wasn’t with him that day. Perhaps he was checking road conditions before they drove to town together, or perhaps he was getting a coffee at the New Harris Store. His son Patrick told me the family went armed for months, believing the cartel was after them.

Friends remember Dick Drewry as a kind, gentle, soft spoken man. He graduated from the Cal Poly SLO, served in the military, worked for the county, and ran the home ranch all his life. He and Phyllis adopted two sons. He was a gentleman, kind to all his neighbors, including the hippie newcomers. One Bell Springs resident told me he would always pick up a hitchhiker. He was, in the parlance of the area, an “old timer,” which is a term of endearment and respect. There are very few photos of him left. I was only able to track down a few. One of his relatives told me many of his photos were lost in a house fire. His wife Phyllis died shortly after Dick’s murder.

A cowgirl named Jenny runs cows over on that part of Bell Springs. She is blonde and tough as nails, another person Orange County wouldn’t believe. Working out there, she says she has had guns on her while she works since she was a girl. Once her sister’s cows got out; she came back to find them decapitated, their heads stuck on fence posts.

She says the last time she spoke with Dick, he pulled up next to her in her pickup and chided her. “Honey I don’t see your gun,” he said. He reminded her she needed to be packing up there, always.

Whatever happened to Dick Drewry, he knew his neighborhood was dangerous. Maybe he knew someone was out for him. Maybe not. It seems he rolled down his window to speak with his killer. Within days of reminding Jenny to carry a gun with her wherever she went, he was found dead, with no gun in his vehicle.

“Water is your motive,” Jenny told me. “Water is going to be the motive for a lot of murders.”

In this part of Northern California, water is always scarce. The government is taking out hydroelectric dams that the communities rely on for water supply in order to facilitate the habitat of some fish, even as a constant flow of organized criminal groups bring labor across the Southern border to meet increasing global demand for marijuana. The government does nothing to stop it. In Mendocino County, ranchers go armed, living in fear, now forced to worry about the water systems they have built over generations to care for their cattle. To my knowledge, Gavin Newsom still has not returned those phone calls.

Paradise Lost

Growing up, we knew all the neighbors and all the neighbors’ gate codes. We used to swim in the irrigation ditch, ride green horses all over the hills. We picked wild blackberries and made jam, went to church on Sunday. We had friends whose parents grew, friends whose parents ranched.

“You know the way the rumor mill works,” a neighbor said to me. “Anything unexplained is blamed on a stranger, the cartel, some ‘other,’ not us. Always someone else.”

I thought this would be a documentary about organized crime, the global drug trade, the open border, coming into my beautiful little town and destroying it.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn wrote, “The line separating good and evil passes not through states, nor between classes, nor between political parties either—but right through every human heart.”

Greed is corrosive. Maybe it was greed that attracted bad actors. Or maybe it was greed that turned decent people bad. The structures we sacrificed for a new and better American dream ended up mattering most when they were gone. Maybe the loss of community led to silence, and then our silence killed whatever community was left. Whatever may have happened before January 26, 2021, all I know is that on that day an old man was killed in his car on a snowy morning—an old man who raised cows all his life and welcomed his strange new neighbors, killed in the same place he was born, except now it was entirely different, a place where a neighbor can be murdered and no one will talk.

The hippie movement set out to bring paradise on earth, remade in man’s image. We would do away with all the rules and structures honored since time immemorial by square communities like the cowboy towns of Mendocino County. We thought we could remake Eden and escape evil. But evil found our garden, too.

Watch High Country Murder

High Country Murder is a production of Palladium Pictures film incubator. Directed and produced by Keely Brazil Covello and Michaela Brazil Gillies. Director of photography Ryan Francis. Editor Ryan Francis. Creative producers Graham Kelley and Ryan Francis. A Go West Media production in association with Naknek Films.

OK, I’m gonna sound like a meathead, but I gotta say this. If there are people going up into the forests and hills to do gangster crap…it’s time to send in the 82nd Airborne and the 101st Airborne and the 10th Mountain Division and run those bastards out at gunpoint or bayonet point. This is our country - let’s act like it!

RIP Dick Drewry. My heart breaks for the decent people in the area who are suffering at the hands of dirtbags from out of town.

Living on a high ridge in Mendocino County, I had read about this murder in the AVA and Redheaded Blackbelt. Thank you for sussing out and telling this story.