Is There a Conspiracy Against Ranching in the Federal Government?

For many American producers, the eviction of 12 ranching families on Point Reyes is just the latest chapter in a long march to erasure.

In the town of Bolinas, just south of Point Reyes, Billie Thibodeau runs a grazing-for-hire service, cleaning up fire fuel.

This stretch of California was once a blue-collar promised land on the razor edge of America. It is fast becoming a ghost coast—summer homes for billionaires, trails and weekend photo ops for the leisure set.

When Thibodeau first arrived, she was struck by a series of abandoned Victorian farmhouses in apparent disrepair. She couldn’t understand why so many farms and ranches stood empty. She began asking around.

“Nobody owns these ranches,” she tells me. “The government owns them. They were basically stolen from the original owners by eminent domain in the early 60s. One of these farmhouses looks like it has government officials living in it. I see Parks vehicles there all the time. It’s been totally trashed. There’s a lot of stories of how they’ve gotten rid of the ranchers here.”

Some Californians believe designating this land protected wilderness is vital to the future of a desirable coastline otherwise vulnerable to development pressure. Others say paving over the bones of 150 years of agricultural history disregards food production and security—banal concerns these expensive zip codes may expect to be relegated to the poorer parts of California, not their tony backyard. For locals who worry about this erosion, the removal of 12 ranching families from Point Reyes National Seashore is just the latest chapter in a vast conspiracy against independent agriculture.

“It’s environmental terrorism,” says Andrew Giacomini, an attorney representing the farmworkers on Point Reyes. This month, he filed a lawsuit alleging that the National Park Service conspired to pay off ranchers and turn their leases over to an environmental group. “I believe there is a total conspiracy going on with environmental groups and the National Park Service to end ranching on national parks, and this is their playbook.”

Rumors of an Anti-Ranching Conspiracy in the Federal Government

Many of my sources believe federal agencies like the Park Service have a pattern of strong-arming producers into surrendering their land before terminating promised agricultural leases and forcing them out.

“The Park Service hates ranchers,” one tells me. She has close personal experience with the agency. I’ve agreed to keep her anonymous. “They lure people in, but when land has National Park or National Seashore status, ranchers have no rights or freedom anymore.”

During the years the Point Reyes ranchers were stuck in limbo with lawsuits from deep-pocketed environmental groups, the Park Service portrayed itself as a passive party.

“The Park Service works very, very hard to maintain its Ranger Image,” says Sarah Rolph, a writer who is authoring a book about the closure of Drake’s Bay Oyster Farm on Point Reyes. “They never get their hands dirty, they farm out the work of creating and promulgating the relevant false narrative to the activists, and then they collude behind closed doors in the course of their fake lawsuits. Sue-and-settle—it's a known scam.”

My anonymous source concurs.

“I believe these non-profit environmentalist groups and the National Park Service are in bed with each other. The environmentalists play the bad guy and the Park Service tries to play the good guy. But they’re not. They’re extreme zealots.”

Gag Orders, Whistleblowers, Warnings

In 2006, former park superintendent of the Channel Islands Tim Setnicka wrote a three-part series for the now-closed Santa Barbara News-Press. At the time, there was a debate over what to do with remaining deer and elk populations on the islands. The Park Service wanted those animals exterminated (eventually, they were).

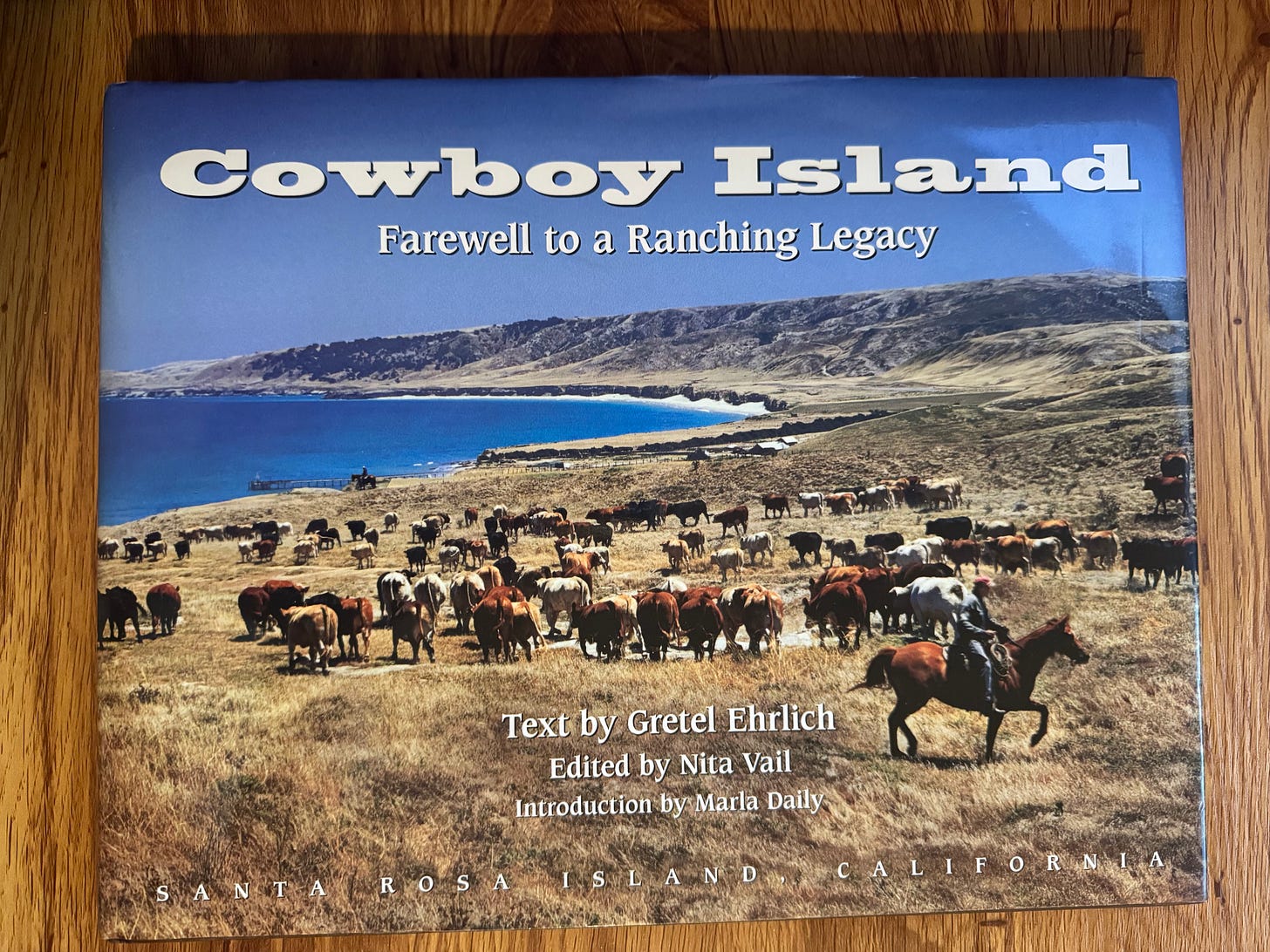

In detail, Setnicka described the actions of the National Park in acquiring the Channel Islands and their “secretive and suspect management practices,” as the editor put it. He claimed to spill secrets, outlining a playbook that sounded more like a pitch for a thriller screenplay. He recounted what he witnessed on Santa Rosa Island, where Vail & Vickers ranch was forced to sell.

For example, he described how the Park Service used water samples as leverage:

To aid in our quest for ways to lever the Vails’ cattle ranch on Santa Rosa Island to reduce deer and elk numbers, we contacted the Regional Water Quality Board (RWQB) in San Luis Obispo.

We expressed our “concerns” about water quality on the dozen or so streams on Santa Rosa. We took these water board officials to the island and showed them the worst possible cases of cows in the dozen or so year-round creeks, none of which ever flowed enough to support fish populations. In the summer time, these creeks were nasty, fouled areas with the cattle hanging down in the canyon bottoms near the water sources.

We used the same bi-directional information flow that we did with the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service to get the water board the information to become involved on Santa Rosa Island.

It worked again. Within two years, the Regional Water Quality Board issued the state of California’s first ever Clean Up or Abatement Order (CAO) against the National Park Service for non-point source pollution for a ranching operation.

The water board did not issue or name the Vail ranch, which would mean taking the ranching community head-on. All ranchers and farmers should note their action.

Instead they issued the CAO against me and the Park Service—a very transparent action on their part.

Once the park was under a CAO, the water board ordered me and the Park Service to “clean up Santa Rosa Island streams” and begin a water-monitoring program to document progress. So we spent hundreds of thousands of dollars documenting that island streams which have cattle on and alongside their banks are more heavily polluted than small stream areas where cattle were fenced out.

We proved and documented the obvious, with taxpayer funds, and gave the information to the water board which, in turn, used it to hammer the Park Service and our “tenants,” as they referred to the Vails.

Setnicka also detailed how the Vail family was betrayed. After being promised a long-term lease, the Park Service began to renege.

[Al Vail] charged that the park service and its “partners” were not negotiating in good faith and were using “biased information” to fuel the ESA and Clean Water Act “as hammers against us.”

He frequently reminded everyone that when Channel Islands National Park was first proposed and established, during the congressional hearings in 1979 and 1980, the park service acknowledged and thanked them for taking care of the island to the point that Santa Rosa Island merited inclusion into the National Park Service.

“Once you guys got title (to Santa Rosa Island), now we’re the enemy who is destroying the island,” Al Vail said. He also reminded me that Santa Rosa Island was the Vails’ home for almost 90 years and “…if we’d overgrazed or destroyed it, we would be (expletive) where we eat.”

Perhaps more to the point, Al Vail would also frequently ask various managers and legislators, “How come when you wanted the island you kissed our asses, and now, after you got it, you are trying to put a sharp stick in our eye?”

No one had a good answer for him.

My opinion, as articulated by another National Park Service superintendent that I know, was that the park service, as well as all government, has “no soul.” Government is only as good as the people filling the ranks.

And who watches over the National Park Service during these events? No one.

Ultimately, Vail & Vickers was no match for the full force of the federal government. After 90 years of ranching, the last steers were shipped off the island in 1998 in the. Vaquero II, a cattle boat since sold and converted to a private yacht.

In Cowboy Island, her pictorial memoir of Vail & Vickers, Gretel Ehrlich wrote about the last day on the ranch:

It is difficult to understand what is happening here. Two families are losing a century’s worth of hard work, love, and nurturing. The island feels empty. No more cattle on the range and the horses are all corraled and settled.

Except one. All night a sorrel gelding gallops back and forth along the low fence near the ranch house, whinnying for the mare he loves, but from whom he’s been separated. By morning, he is in with the corral of saddle horses that will be shipped to the mainland today.

In the red barn, a row of dusty saddles goes unused. Ravens throw themselves into the sky as the Vaquero II comes, accepts its final load. The horses stand patiently in the open holds of the boat, innocent and good-hearted as always. As the Vaquero II pulls away, the windbreak at the edge of the island heaves and sighs, waving goodbye and beckoning the horses to come back home.

Al Vail, the patriarch of a rich ranching history, passed away within months of his forced removal by the federal government.

On nearby Santa Cruz Island, the federal government sent a Blackhawk helicopter and 20 armed officers to raid a hunting club over alleged Chumash Indian grave robbing—though many locals believed the raid had more to do with a stubborn 82 year-old landowner named Francis Gherini, the last holdout on the Channel Islands.

“You’re next.”

Setnicka signed off on the Santa Cruz raid. Later it seems he had seen enough to reverse his stance on the Park Service. He believed a bad fate awaited Point Reyes.

In 2014, he held a meeting at a Marin County school where he warned the ranchers that what he had seen on the Channel Islands was not an isolated case. He said Point Reyes was next.

Like the Vails, the Point Reyes families had been assured long-term agricultural leases. Setnicka claimed this promise was empty. He stated in no uncertain terms that the National Park Service was coming for them.

A reporter for the Point Reyes Light wrote at the time:

“Mr. Setnicka framed the park service as a clandestine government agency that ignores data and is hostile to ranching…According to Mr. Setnicka, much of the inter-agency work was more or less orchestrated to help bring about the end of ranching.”

Community members tell me they remember hearing Setnicka’s warning. They had hoped he was overreacting.

Setnicka declined to comment for this story.

Writing on the Wall

The push to turn Point Reyes into a recreational area began in the 1930s, when San Francisco’s upper crust began scouting bucolic retreats a short drive from their growing urban center. They settled on a desolate peninsula where immigrant ranching families had been scratching out a hardscrabble life since the Gold Rush.

“All of our families were essentially threatened with eminent domain,” a daughter of one of the Point Reyes ranchers tells me. She also speaks on condition of anonymity, and only about the past. “We did not want to sell but sold out of necessity. We did it under the understanding that we would be leased back the land indefinitely.”

Special interest groups like the Sierra Club pushed for the government to seize this land. Wealthy patrons from the Bay Area joined to elicit public pressure and funds from all over the country.

Rolph says a similar method is still used today.

“These environmental groups have tons of money,” she says. “They get donations from corporations and from individuals, and now that they can use online marketing to spread their creepy campaigns, it costs less than ever to orchestrate them. You'll see the anti-ranch crowd claiming that the public was heard, that there were thousands of comments all against ranching on Point Reyes. Those thousands of comments were orchestrated by the groups themselves. You can trace the narrative just by noting the words in the comments that match the words in the anti-ranch press releases.

In 1961, Zena Cabral, widow of longtime Point Reyes dairyman Joseph V. Mendoza, the traveled all the way to Washington, D.C. to plead her case.

Her speech to Congress was documented by a local historian:

“I was not born in this country. I was born in Europe. But since I was a child I wanted to come to America, to the land where there was respect for human dignity, the land of the free…where the minorities would not be trampled on, where there would be no dictators.

[Point Reyes] is where my children were born…and my grandchildren were raised.

…Now I am faced with the possibility of losing everything that I have worked for. The strangest thing is that I never was approached. Everything was done underhanded…Nobody ever came to me to ask, ‘Do you want to sell your property for a park?’

…If my ranches would be taken for defense, well, you have to sacrifice, but it is for the benefit of all, for the benefit of my family as well as for the others.

But for recreation, what kind of recreation did I have when I was a youngster? Work and save so my children would have a sense of security and heritage that I felt belonged to them. Now every inch of my land is supposed to disappear.”

Despite Zena’s much-publicized plea and the ranchers’ entreaties, the land would officially become a National Seashore in 1972. The government assured Marin County that agriculture would remain part of the legacy and fabric of the peninsula.

Warning Shot

In 2012, the government announced the closure of Drake’s Bay Oyster Farm on Point Reyes. The Lunny family had operated their business for years, producing over half the oysters in California, before they fell out of favor. Critics say the Lunnys were victims of junk science; oysters filter the ocean and have a positive impact on water quality and marine life.

During his first term in 2019, President Trump invited Kevin Lunny to the White House.

“We’ll have somebody right here in the White House looking at it, Kevin, so this doesn’t happen to other people,” Trump told him. “You’re really brave to be here.”

Trump signed an executive order meant to protect farmers from similar overreach.

“The National Park Service forced our oyster farm out of business,” Kevin Lunny said. Behind the presidential seal, he admitted he was afraid for the Point Reyes ranchers. His family also ran a cattle operation. “Our fear is that those families may be facing what the oyster farm faced.”

Donald Trump promised the White House would protect the Point Reyes ranchers. Then he lost his re-elect bid in 2020, and a new administration came into power.

After it was announced the ranchers would be leaving, Lunny’s speech at the Point Reyes Town Hall received hundreds of thousands of views online.

“It’s who we are, it’s our existence, it’s our identity, and we have to walk away from it,” he said. “I know it could have ended differently. But we had the wrong people in the room making decisions and everybody else not allowed in.”

Does the National Park Service Have a Playbook?

Three environmental groups sued to stop the Park Service from granting renewed leases to the ranchers on Point Reyes: The Center for Biological Diversity, Resource Renewal Institute, and Western Watersheds.

“The farms are actually an asset to the park and to the environment,” says Albert Straus, CEO of Straus Family Creamery and one of the most vocal advocates for the farmers on Point Reyes.

Straus says there has never been any evidence that the ranches and dairies caused environmental damage, as demonstrated by the results of a National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) review.

“We’ve shown that we live in harmony with nature, not adversely, and farms which have been there over 150 years have been the thing that actually kept nature intact.”

Undeterred by the NEPA review, the plaintiffs sued again, calling on the Park Service to remove the ranchers and expand elk herds.

“These non-profit groups all seem to have a playbook,” says my anonymous source. “They find vulnerable people who can’t afford ongoing litigation—ranchers, farmers, developers—and attack them. They sue with the goal of forcing them off the land, knowing the ranchers can’t fight back. The ranchers can’t do infrastructure repairs. They face extreme pressure. These groups have unlimited money. After they force the victim to settle and leave, they take massive amounts of taxpayer-funded settlement money.”

This source tells me the National Park Service uses Department of Justice lawyers.

“The environmental groups are in bed with the Park Service,” she claims. “The Park Service feeds the environmentalists information. The Department of Justice also feeds environmentalists information.”

Giacomini points out that the case should have been winnable. The fact that it wasn’t suggests the Park Service wanted the ranchers out.

“The National Park Service chose not to win,” Giacomini states. “When does the federal government fold when it has a winnable case? When it wants to.”

“The National Park Service chose not to win. When does the federal government fold when it has a winnable case? When it wants to.”

“They held all the cards. They played those cards. They put pressure on the ranchers and got exactly what they wanted. Pretending they’re a bystander—it’s such a lie.”

The Park Service did not respond to my request for comment.

Giacomini’s latest lawsuit, filed with the United States District Court for the Northern District of California, alleges that “the National Park Service, Acting Director, and Regional Director conspired with the Conservancy to pay off the departing ranchers in exchange for the ranchers relinquishing their rights to 20-year leases and instead leasing the ranchers’ property to the Conservancy.”

Heather Gately, communications director for the California branch of The Nature Conservancy (TNC), tells me the organization did not pressure the ranchers in their decision. Although not involved in the initial lawsuits, the organization stepped in to find some solution between the parties after a years-long stalemate.

“TNC agreed to see if it could help resolve this longstanding conflict and did not come with any preconceived expectation or agenda about the future of the ranches or what the litigation parties would agree to,” she says.

In his public comments at the Town Hall, rancher Kevin Lunny expressed gratitude for The Nature Conservancy’s role, saying he believed they had good intentions.

The Nature Conservancy has stated they plan to continue a grazing program on the peninsula after the ranchers leave to manage fire fuel. I ask if they are concerned about lawsuits from the same environmental groups, once again alleging damage caused by grazing, but did not receive a response.

Under the Wire Before a New Administration

The ranchers on Point Reyes are afraid speaking to me will violate their NDAs.

When I ask my anonymous source with knowledge of past Park Service dealings about these NDAs, she tells me both sides are bound, but she sees a double standard.

“The Park Service leaks what they want into the media out of these cases despite those gag orders, while enforcing gags on the ranchers.”

Straus describes the Park Service as a hostile landlord. He believes the Park Service turned up the pressure in order to get the ranchers out before the new Trump administration took office.

“The farmers didn’t want to leave their home,” he tells me. “They didn’t want to leave their businesses. But not having a landlord that was really there working with them was not sustainable.”

“I think it was very obvious that that’s what the intent was—to get it done before the new administration,” he adds.

I ask Giacomini if he also believes the lawsuit, which lagged for years before experiencing a seeming injection of energy before January 2025, was timed to slip under the wire in the final days of the Biden Administration, before Trump had a chance to change leadership at the Department of the Interior.

Giacomini’s answer is succinct. “100%.”

Farmworkers Caught in the Crossfire

The closure of these dairies and ranches is a significant loss for the original working communities and agricultural heritage of Marin County.

Giacomini says the settlement agreement requires the ranchers to evict all the farmworkers living on the peninsula in order to get paid.

“We believe the deal the NPS orchestrated is illegal,” he tells me. “The way NPS set this whole thing up, they pressured ranchers to get rid of their leases, brought The Nature Conservancy in to pay for it, and as part of that expect the ranchers to evict everyone who lives there or they take a big haircut on their payment.”

Gately of The Nature Conservancy contests this interpretation and says there is a fund for farmworkers, funded by the mediation parties, to support their transition.

If the farmworkers are evicted, Giacomini claims employees of The Nature Conservancy and Parks will move into their housing. He confirms that Parks employees are living in buildings that were once privately-owned farmhouses.

“A lot of historic farmhouses and barns in the area have been shuttered. They haven’t torn them down because they’re designated as historic buildings and can’t be demolished. But the Parks Service doesn’t have to work to keep them up. They just paint them white, board them up, leave them to go fallow. The National Park Service has employees living in lots of those buildings.”

The Point Reyes ranchers have told Giacomini they will not evict the farmworkers, even if it means taking a cut in their payout.

“I believe them,” Giacomini says.

Straus points out that there is already a shortage of affordable housing in Marin County. Agriculture requires an ecosystem, including farmworkers and skilled repairmen. Slowly, those workers are being driven out of the community, as billionaires buy up working landscapes for hobby farms and ranches.

“Over 80% of the workforce commutes in,” he says. “We're just on the verge of collapse. These actions are putting a stake in the heart of our community.”

Once a model of organic farming for the world, so renowned that agriculture aficionado King Charles brought Camilla here for their honeymoon decades ago, he says Marin County has now become a “playground for the rich.”

“This is not isolated. This is happening all over the country.”

California’s Ghost Coast

Driving her sheep and goats to graze firebreaks near the ghost ranches of Point Reyes, Thibodeau says this area of California is special—not in spite of generations of ranchers, but because of them.

“I graze land all over this area, both north and south of San Francisco, and this exact location has the healthiest soil I’ve ever seen in my life. This is special, special land. The ranchers have built topsoil over generations and it is so valuable; people don’t see that. Ruminant grazing has built this topsoil. The Parks Service is disrespecting it.”

She says humans rely on ruminants, and the land needs ruminants.

“If you allow grasses to grow without being grazed it’s just pulling nutrients out of the soil without putting anything back into it. I can show you places that have gone fallow for maybe five years and you can already see the process of land and soil degrading.”

I’ve asked most of the folks I’ve interviewed why the Park Service would want to do this. What is their motivation? No one has given me an answer, except Billie.

“It’s an agenda to get people off the land. It’s a movement to extract people from our most valuable resource, which is the land. This land is power. Ranchers hold a lot of power. The government is afraid of it.”

I am beyond impressed with these articles and the level of honesty provided. The method of these agencies begins as far back as elementary school now with the indoctrination of "humans= bad and the re-wilding movement. I can't stress enough how working lands are healthy lands and without active participants with experience and knowledge, the succession of grasslands turns to woody shrubs and eventually to over-rested forests. We need able-bodied men and women to help keep working lands alive because it's their work that feeds us and keeps us alive.

This Isa epic tragedy. As someone who has traveled all through that area , it a horrendous action by the Feds